interview with PETER DASZAK

How are you doing today ?

I was lucky enough to see the recent documentary blame , by Christian Frei. A beautiful film aesthetically and very interesting on many different levels, but your involvement with WIV and the defuse grant has been the subject of endless discussion for years, I was more interested that people can get to know you as a person.

We are, I think, more or less the same age, both grew up in the uk , so were probably exposed to the same culture of the time.

What do you think of when you look back on growing up in Manchester? Beyond your obvious early passion for zoology, did you have other interests?

Peter: My thoughts looking back on growing up in Manchester in the 1970s and 80s are a real mixed bag. First, I’m proud to be a Northerner, from the grim Northwest of England. When you’re brought up on the outskirts of Manchester, it gives you strength when you’re under pressure. You know what hardship can be, and it takes a lot to shake you. On the other hand, looking back on it, my hometown was a harsh environment. Now that I live in the USA outside New York, with black bears and coyotes in my back yard, and a short drive from expanses of forest that just didn’t exist in the North of England when I was a kid, I realize I was growing up in a post-industrial decaying environment. We rode our bikes on what we called ‘the bottom fields’ but what was actually a former coal mine, and the hill we used to freewheel down as kids, was actually a slag heap – the tailings from a disused coal mine. Shocking really, but we loved it as children. I look at stories coming out of Manchester – it’s just a gritty, hard place politically, socially and economically – Dr. Death (Harold Shipman, a medic who killed probably >100 people) practiced a few miles from our house and one of our neighbors set up a ‘Free Harold Shipman’ campaign when he was first arrested, until he realized the allegations were true. It was hard and gritty for nature too, but you got to see nature beginning to bounce back with disused factories and railway lines being overtaken with brambles, moths and butterflies, a pair of jacksnipe in the polluted water coming out of the coal mine tunnel etc. That brought me joy and I found it fascinating.

My hobbies were always exploring nature – hiking in the moors behind Manchester, a bit of rock climbing, bird watching, catching and breeding moths, frogs, newts, keeping and breeding imported reptiles. But I developed other hobbies as I grew older – I was there in Manchester just at the peak of punk rock, and managed to get into gigs in town with my mates, a couple of years under age. I ended up getting into Thai boxing up in Manchester too – I’d never really been into sports other than a bit of long distance running, but I really enjoyed it – the purity of it, and the way you have to face up to the real fear of getting punched and kicked…

My whole time in Manchester was an interesting time politically and socially in the UK as you know. I grew up through the age of worrying about nuclear war, of Thatcher and the poll tax, of mass unemployment. But there were some great positive things too – we had basically free university education if you weren’t from a wealthy household. Those were great levelers for our society back then. I got a scholarship to a good school by passing exams, then a free university degree. You had to work for it, of course, but there was a real sense of freedom to explore life that came with that.

The last 5 years most of been incredibly difficult and stressful for you. What, if anything has helped you get through it all ?

Peter: I don’t think people realize how bad this stuff can get. It’s not the actual threats, or the real risk of losing your income etc., it’s more like the sort of impact you read about with school bullying. Essentially, you get singled out and attacked verbally, online, in the press. People pile on and support the attacks and start to look for new ways to harass you, and it gets worse. Meanwhile you rapidly notice that most (in the end almost all) of the people in your network, the institutions and leaders who have supported you, and even those you thought were good friends, start to move away. They don’t want to be attacked, so they just turn the other way and let it happen. It’s a deep sense of betrayal and makes you very angry and sad. I developed a system for coping that was a sort of mantra (still is) – basically, I rationalized things – there are different layers of health and wellbeing that you need to look after, so you begin at number 1 – is this bullying affecting your health? You look after your bodily health and hope your mental health will benefit. 2 – is this affecting your family? So you make sure that stays strong. 3 – is it affecting your mental health? So you work on making sure you don’t drift into depression and suicidal thoughts. 4 – is your job secure? You work on making sure that you communicate regularly with you bosses and supporters and funders so they stay in support. Everything else is just extra.

At all stages of this miserable journey, I’ve tried to step back and logically think through what’s happening and what I will realistically be able to salvage. This isn’t really an attack on the scientific research I do, or the results or the oversight or the collaborations. It’s a political attack that uses any tool possible to win. They work hard to undermine every aspect of you and what you do – your family come under attack, they interview everyone you’ve ever worked with, they harass the editors of journals, they visit your brother in Sweden and in the UK, they set up websites full of hate and lies, they call you in the middle of the night to wake you up and ruin your day, they threaten you so (they hope) you’ll worry about your safety all the time. So you realize that whatever the outcomes, you’re going to lose a lot in the process. Logic says you should fight hard to preserve as much as possible, but at the same time, you can’t let the damage to your career and loss of income ruin your health, or family, so you don’t dwell on what’s lost – you fight for a future, and work to build back what you can.

One thing that really did help me through some dark times, and remains a source of comfort and hope is that throughout the barrage of attacks, I’ve maintained my objectivity and ethics as a scientist. The work I do is scientific research. That means we collaborate with other scientists, get results, analyze them, then publish them. Time and again we came under real pressure to release data before that process was complete, to cut corners and undermine the normal scientific process. I never did that, even to the point of refusing to hand over sequences to the FBI until they were published. There are dozens of instances like that, most of which will never by known publicly, but they give me solace that I did it right, even if the damage is intense.

As you know, I’m an artist and underground cartoonist. I have corresponded with R Crumb a little, and I’m currently working on a book on his brother Maxon . A very interesting family, and from my

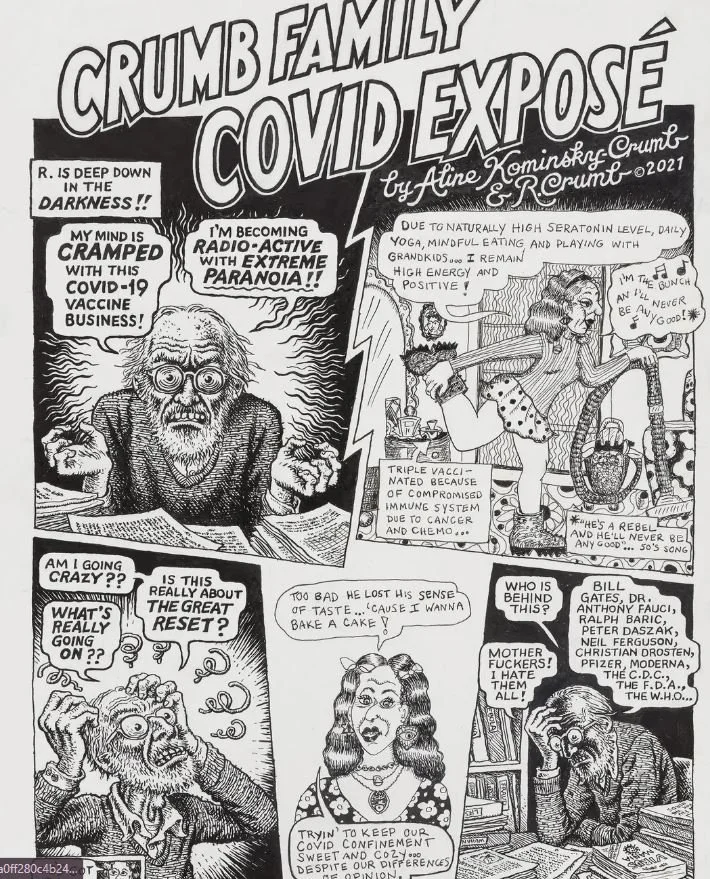

interactions with him, he is a very nice and unique person and artist. What did you think when you saw yourself in his most recent comic book?

Peter: I’m a cartoon fan – I respect the art, the dedication and the power of a well-drawn image. I used to get 2000AD every week when I was doing my Ph.D and couldn’t believe how cartoon art had become so incredibly striking – I remember the Judge Dread images were so indulgent and beautiful – double page center spreads with high quality watercolor paitings. So I knew of Crumb’s cartoons, and of his curious lifestyle. When I saw my name in his book, I was both shocked and honored, to be honest, even though it’s not exactly a compliment. He basically said he was struggling to sift out fact from fiction during the COVID pandemic, so I wasn’t really bothered by that – I think most non-scientists were probably having trouble understanding how an invisible virus is ruining their world.

I can’t imagine being shot from relative obscurity in an important but quite niche field or research, to this almost cartoon like villain. It must of been very disconcerting, has it effected how you see the world?

Peter: Yes. I’ve become far more cynical about politics, progress and who is in power in the world. I guess you could say I’ve become far more aware of it. I read a story in the press and think, yes, but what’s the other side to it, how much of this is just journalists pushing a narrative. I see people pilloried by left wing reporters, and think ‘yes, that’s right’ but then remember that the same reporters believed the lab leak, so how objective are they, and is this story also them buying into some bullshit narrative. If you’re publicly placed in a fake conspiratorial story day after day for more than 5 years, you realize that these conspiracies are part of our fabric as people, and you reject them. You realize that most movies, many novels, and a lot of the stories in the press are based on conspiracies that people either find comfort in, or are being fed by nefarious forces. It’s particularly obvious in the USA in the era of Trump, when your neighbors and half the public get their news from facebook, Twitter or some other alrogithm. I’ve read deeply about why this happens, what the warning signs are, and what can be done to pull through this horrible age we’re living in, where we can’t distinguish fact from fiction, and even if we believe completely upside down BS, we manage to live a normal life (ish). This has been weaponized politically around the world to suit a continuation of 1990s economic and tech growth mindset that is just unsustainable. That’s the problem to me. We’re wilfully destroying our future on this planet, while fooling ourselves that everything’s fine.

We have both travelled a lot, obviously for very different reasons. Yes , cultures can be very different, but, it’s my opinion that people are more or less the same whether you go. Have you found that in your travels around the world?

Peter: Yes – totally agree. People around the world are dealing with the same forces we’ve all had to deal with. They’re struggling to be healthy, prosperous and to help their children grow up into a better life. They’re manipulated by politicians, by corrupt power-brokers, by religious leaders. They find joy in their lives when they can, no matter what the situation, and they want to welcome foreigners and share their stories and cultures. I’ve always found great rewards in getting to know people in every country I’ve worked in – not just the scientists we collaborate with, but spending a bit of time to talk with everyone you meet and get to understand what they’re going through.

Years ago, there was a book called “ amusing ourselves to death “. More and more people references about reality seem to be based on pop culture, a highly curated and almost Simulacra version of life, do you think this cultural phenomenon has played a part on how some people have seen you? Or do you think it would have been more or less the same case 200 years ago. ?

Peter: I definitely get the feeling we’re living a false reality at the moment as a culture in Europe and the West. I guess I see the same in other countries I visit too – especially in urban lifestyles. People are just obsessed with the influencer culture, the idea that people out there have a better life than them, and watching it and dreaming about it. It seems so mindless to me. But, thinking it through, it reminds me of the way in the UK people follow what’s happening with the royal family – their ups and downs – as a way of helping them work through their own trials in life. Maybe, in the end, it’s just normal for us, a sort of hero worship of pop icons and people who’ve bothered to spend their whole lives showing everyone what they do every day online. I’ve never been interested in it. I’ve never worshipped heroes.

I can only imagine it’s easier to see the world in a very binary way, which is why perhaps superhero comics become so popular after the war. Is this just a natural tendency in most people, or do you think it’s manufactured to a degree?

Peter: I think it’s natural for us to categorize as good or bad – it makes life easier. But it’s definitely pushed by outside forces, and it’s quite bizarre when it happens to you. In 2021, we started working with a communications professional. He told me that speaking out publicly is far more useful than staying quiet, because you get to confront the people who are being told youre a villain, with the realities of what you really are – a scientist doing your work in a completely normal way, living a pretty normal life, and just trying to continue it all. It definitely helps, but given the huge pressure and well-funded political activism behind the way I am portrayed as a villain, all part of the obvious political attacks on Fauci and Biden, you can’t win that battle..

How is your family doing? It must of been difficult for them, have they found their own ways of coping with all the attention and attacks?

Peter: They’re doing well, though there are definitely impacts on all of us. We developed ways of coping with it all. I stopped talking about the attacks, and try not to mention each one as it’s happening, and try to fix them with colleagues and supporters. That way, we all get some break from the pressure.

I can see you are fond of gardening. Does your wife enjoy it as well? What about it do most enjoy?

Peter: It’s my thing really, since I was a kid. I just enjoy the way you can take a miserable patch of land and turn it into something beautiful, a miniature recreation of nature. It’s hard work, and you need real

patience because things might take a few years to really come into their own, but it’s a great sense of achievement to resurrect a rundown garden.

In the documentary blame, Christian does a very good job at just showing you, and dr linfa wang and dr zhengli shi as , though extraordinarily talented in their work, but also very ordinary people. And of course you must of developed friendships. It’s a very sad situation that friendships have become destroyed. Do you have any hope that one day you will be able to return to that or do you think the experience of the last five years has fundamentally changed important relationships?

Peter: I think the last 5 years have changed friendships in different ways. For some, like Linfa, Zhengli and other collaborators also being attacked, we have a bond that won’t be broken. We know what really happened in our research – what ‘really happened in Wuhan’ – and we know what these attacks are like. We don’t talk much, and I wonder if I’ll ever see Zhengli or Peng again at this rate, but I know what they’re thinking about all this, and they also know what I’m thinking. For others, in some cases these attacks have pushed us closer together, for those who’ve been going through the fights day-by-day with me. For some it’s pushed us apart, as they’ve looked at their own careers and either purposefully, or more likely, by default, allowed themselves to cut off contact and turn the other way. I think some people just don’t know how to talk about these things, don’t know what to say, but others are more calculated and realized there’s a chance they’ll be attacked too

I have never been to the USA . The politics have always seemed quite alien to me, but I also understand it’s a very beautiful country in a lot of ways, what are some of things you enjoy about living there?

Peter: Not much at the moment to be honest. I came to the US first in 1995 for a conference in San Diego. I’d been collaborating with the vet pathologist at London zoo for a few years, so set up to do a talk and behind the scenes visit at San Diego zoo. It was a real eye-opener- they had the very best reptiles, they were breeding Komodo dragons, they had Boelen’s pythons. The walk to the zoo from the hotel was through a botanical garden with hummingbirds – it was like paradise. I remember flying back to London on a Saturday morning and as the plane came down through the clouds, I saw some people playing cricket on a grey overcast day and the comparison was just not good. When I moved to the US, our work on chytridiomycosis, a fungal disease that caused extinctions in amphibians, got accepted into PNAS – we put out simultaneous press releases in the UK and the USA – in the UK we got a short paragraph in the Times, in the USA we had multiple stories in national press and I was driven down to CNN in Atlanta for a live interview on air. The difference to me summed up why I moved to the USA – new ideas in science and other fields are given a fair shot, supported and funded, and the public seemed to be interested and proud to read about advances in science. That’s not the case right now. The USA has lost its way as a global leader in science and the environment and all of the bullshit around international collaboration just opens up the slot for other countries to step in. What a shame, and what a tragedy.

I still get enjoyment out of being in the USA. First, the nature and countryside is fantastic – real wilderness areas close to cities, nature that is coming back from declines led by deforestation and pollution, and it's so easy to get out there and enjoy it. I’m now a serious skier – in the UK you had to be wealthy to learn to ski – flights and hotels in the Alps. Here in the Northeast, it’s on your doorstep, and it’s gritty and hardcore. Second, there is still plenty of fight left in the decent people of the USA – people who believe in democracy and the rule of law, and those who respect science. So, I’m now spending my

time supporting and building those efforts to try to bring back the US to a more realistic role in global science and environmental health.

It seems from your childhood dreams, for a long time, and hard work, you managed to fulfill a lot of what you dreamed of back in your youth in Manchester. Given all that has happened, and it’s probably a different question to answer, if you knew how everything turned out, would you have done anything differently?

Peter: Hard “No” on that. I’ve spent 5+ years trying to work out what’s happening to my work, our organization and my career. Every week, sometimes every day, we would get a new line of attack and you’d be left with a choice – how to respond, what to say, what action to take – and each one of those decisions was careful and based on the knowledge I had at the time, and speaking with very good colleagues and advisors. Each response was based on what the normal scientific process is, and each decision we made, and I made, each comment or response I had, was right based on the knowledge we had at the time. I knew throughout this process what the dangers were. I knew people wanted me out of my job, out of the positions I had on committees, academies, journals. I knew, and know now, that there are people out there who want me to be indicted, convicted and thrown in jail. I faced those dangers head on, and will continue to face the future head on. I won’t be silent, I won’t be harassed, and I won’t kowtow.

One of the things I have found slightly annoying, is that , even among people who are scientific literature, people insist on portraying you as a “ controversial “ figure, but there seems little awareness that it was other people that insisted that there was a controversy, and now they almost seem afraid of seeming bias in not portraying you as someone caught up in controversies that you didn’t create, this must be extremely frustrating. Am I correct in thinking that or have I been mistaken?

Peter: Massively frustrating. It’s the biggest pile of bullshit out there, and this is one of the reasons the negative algorithms, and the awful people who drive all this hate, win (at least in the short term). They attack you by picking at every comment you’ve made and misconstruing, misrepresenting your motives and goals. They accuse you of things that are clearly not true and do this so often, with such diverse conspiracies that it’s impossible to respond to each one in detail. When you do, they pick apart your response and rinse and repeat with more lies and allegations. They then say you’re controversial because of the false controversy they’ve created with lies and false allegations. Then you rapidly find that you’re calendar becomes far less busy with committees and interviews and invitations to this and that conference, because of this fake controversy. Good people fall for it, and that’s the saddest part of all. A few strong-willed folks stand up for you and they get attacked at every step of the way. They’re criticized in the press, on social media, with email campaigns. Their bosses get complaints and they then start getting detailed attacks based on their relationship with you. Colleagues who’ve simply done their best to stand up and defend the science that we have published have now been investigated by those awful politicized congressional committees, sued by nefarious lawyers, lost funding and lost jobs because of it. That’s how a political campaign works. That’s not how scientists are supposed to be treated.

Over the last 5 years, part of my fascination with this topic is the feeling I was witnessing the emergence of a conspiracy theory narrative that will never go away, and I have found it telling, that the over the years, with the work of Dr. Angela Rasmussen, Michael Worobey, Professor Edward Holmes , and many other, that work to pinpoint the origin of the pandemic has been extraordinary, so, some people are reverting back to version of the lab leak of which there is no evidence.

As an artist I have been interested in conspiracy narratives for a long time, have you ever had an interest in them?

Peter: good question and yes, but only as a fictional narrative. I loved watching the overlong movies about JFK’s assassination (very convincing), and I used to really enjoy reading about conspiracies in spy novels etc. But, if you’re a scientist, you become a very avid ‘doubter’. I need to see factual evidence of anything to believe it – I read a story and want to see the primary source, the underlying data before I’m satisfied with the conclusion. It becomes a problem because there is a role for ‘rumors’ in our lives. I think that we listen to gossip because it gets you ready to second guess someone who might be trying to BS you – it’s a social cue, not a scientific one that makes it easier to make quick decisions about someone or something. During the pandemic, when all of our lives were temporarily turned upside down, we all listened to half facts and had to make real world decisions based on them – to mask or not, to go shopping or not, to sterilize our shopping with alcohol or not. Rumors, gossip and conspiracy theories make these decisions easier to make because they allow you to recuse yourself from the potential damage that could happen. With a conspiracy, you blame the upturned life of the pandemic lockdowns on scientists who were up to no good, rather than on your own desire for continued economic growth that ruins the environment and drives the emergence of new diseases. Sometimes, scientists are here to bring facts to bear that are uncomfortable, hard to believe, and require life changing decisions to fix. It’s the same with climate change, and look where we are with that…

When things heat up, as they tend to do every 5 months or so, have you developed any strategies to keep your self sane ?

Peter: Yes – I have my support group of family, friends and colleagues who I can talk with and get advice. I have my strategy of stepping outside of the attack and remembering the bigger picture. I also have the incredibly valuable knowledge that I’m right about our work and that in the end, facts will always support my original conclusion that this thing came from the industrial scale wildlife trade, not the work we did in China.

I have grown used to not being able to fully express my opinions on things, and I think partly why I enjoy comics , is no one takes them to seriously, so, there is a freedom of expression that can sneak in under the radar. Have you found yourself having to self sensor as every word and email seems to be combed over by people searching for hidden meaning in them, how have you adjusted to that if that is the case?

Peter: I try not to, to be honest. I’m obviously very careful and as disciplined as possible when I respond to journalists who are digging with some ulterior motive. I usually don’t bother responding – even when

they seem to be from a fair and balanced perspective, they often just go down the ‘bothsideism’ line, and say something like “However, other scientists disagree …” then quote someone who has zero expertise and a long history of pushing an agenda. It’s a waste of time to respond to them. In emails, chats, and interviews at conferences etc. I just try to be normal and honest – they can pick those comments apart, quote me out of context, use it to form the basis for an attack, but I’m not going to let them silence me.

I often hear that people don’t care where the virus came from, it doesn’t make any difference. My position has been, if you take the most common form of the virus being a bio weapon, it forms a anchoring bias, that casts scientists as these evil people up to secretive things in countries people have most likely never visited and this bias acts as a crank magnet for having a baseline of mistrust. What do you think when you hear other scientists say they don’t really care where the virus came from?

Peter: It seems completely disingenuous to me. If they don’t care, why are they spending time talking to a reporter about it? Usually, they go on to say ‘if it comes from nature, we should close down the wildlife trade etc’ and ‘at the same time, it’s a good thing to tighten up biosafety in labs’. Utterly disingenuous and they know it. The point is that it did come from somewhere and was driven by some activity. It caused millions of deaths and cost tens of trillions of dollars to the global economy, so of course we need to know what caused COVID-19. I’ve spent my career looking at origins of outbreaks and analyzing the drivers of emerging diseases. In our global EID hotspots mapping there are something like 500 emerging disease events. None of the new diseases found in people in the past few decades originated in a lab. The only outbreak that people seem to cite is the emergence of a flu strain in the USSR that allegedly originated in a failed vaccine strain – but the data on that are not complete, and there is plenty of evidence to suggest it was a natural origin. So, if our work is correct, that the largescale environmental changes (deforestation, wildlife trade, climate change, globalized trade, industrialized agriculture) are the causes of almost every single EID event, and every single known pandemic since the Great Influenza of 1918, including COVID-19, let’s face that issue head on, and stop supporting efforts to target lab virology when we’ll be needing lab virology to stop the next one!

Science is hard, and me and most people completely take it for granted. There is a fallacy that everything “ natural “ is as it should be, and should not be “ meddled “ with, probably a lot of well meaning environmentalists fall into this way of thinking. But why do you think people exclude humans from nature? As if we are somehow outside of it ? It may be too much of a philosophical question, but do you ever ponder such things?

Peter: Yes, I think about it a lot. Humans are part of nature. “We are all animals” (great song by the Diagram Brothers). We have an arrogance that we’re above it all. This is best summed up by the bullshit logic of the techbros who bang on about starting a new life on another planet – completely unrealistic of course and meanwhile, we’re burning and polluting this one. It’s also summed up hilariously in that great episode of the Sopranos where the mob tough guys try to kill a Russian mafia guy and dump him in the New Jersey pine barrens in winter. He runs off and they get lost in the snow wearing their crocodile leather shoes and

rapidly succumbing to the harshness of nature. We’ve done an effective job over the past few millennia shielding ourselves from nature with clothes, houses, agriculture, and now with technology, computers, vaccines and drugs. When we’re confronted by nature’s cruelty we demand a tech solution (e.g. the pandemic preparedness plans are more about creating vaccines than reducing deforestation or the wildlife trade). We think we can silver bullet our way out of any challenge – and asteroid (just nuke it), a hurricane (Trump asked the DoD in Trump 1 if they can’t just nuke it), or climate change (we’ll de-carbonize the atmosphere). The last thing we think of is humbly accepting that our influence on our planet is often malign, and reducing our footprint.

Ironically, and sadly, many of the people politically lining up to attack scientists in the USA actually yearn to put themselves back in the right place with nature – they just got it a bit wrong – their version is going out hunting and fishing, living life like back in the 1950s, little realizing our current environmental impact is making that unsustainable or impossible.

As ordinary people, i like to think, most people don’t like being misinformed, and for some reason have a very hard time accepting they have been. Is this a natural human trait do you think, or has it ironically gotten worse because we are exposed to amounts of information daily that our grandfathers would have been in 5 years?

Peter: I think there’s a lot of pride at stake when you’ve been duped by an influencer, or even just the basic drive of a social media algorithm. It’s really hard to say you’re wrong and accept that you’re not as clever or resolute as you thought you were. Let’s face it though, our grandfathers didn’t have social media, but they did have some serious BS delivered to them by politicians and religious leaders that led to a lot of daily horrors, occasional wars and economic disasters.

The Dali lama was once asked what can one person do about any of this, to which he famously replied, have you ever spent the night with a mosquito. What is your reading on what he meant by this?

Peter: I thought that quote was the idea that small things can have disproportionately high impacts. It’s about human arrogance, domination over nature, failure to recognize the validity of a threat – our hubris. For a virus, it’s even more so. I believe one of the reasons people have such trouble accepting the reality of viral diseases is that we can’t see them at all. How can something invisible cause such damage? It’s probably partially the reason why people have such difficulty understanding what an epidemiologist of viral researcher does – they look for evidence of that invisible thing being there and causing damage, they track the patterns of destruction by them and try to predict and prevent future events. That’s very different from most other things in life where we respond to real issues that are visible and actionable. We see a busy road, we wait to cross.

And do you have advice for people living in what has been coined “ the post truth era “ ?

Peter: Yes. First - Wake up and recognize you’re being duped. Read what people who study misinformation are saying. Recognize that the people pumping your social media full of half-truths aren’t

doing this to be your friend or for ‘likes’. They’re doing this to make money, gain fame (and then make money), gain power and prestige (and use that to make money). It’s cynical and malicious, and you are being manipulated for their purposes. In a way, recognizing that gives you real power – you can say no to them by not reading their BS, unfollowing them, not posting links to their articles, and disengaging from the feed more. Second – find alternatives to doom-scrolling. Get outside, look at nature, read a book, write something, visit your neighbor, phone a friend. All of these bring real connections, escape, rewards and joy that the endless likes and clicks of your social media feeds fake to you on a daily basis. They also do far less harm..

Do you enjoy reading? Have you read any good books recently?

Peter: I started reading when I started flying a lot – I decided I’d read the classics that I never bothered to in school. The first book I read was a briefer on communism, and I spent the next 10 years reading biographies and analyses of the rise of Communism, Moaism, the historic changes in Cambodia, Vietnam and across the world in the 20th Century, and novels from the Gulag. My favorite – “Kolyma Tales” by Varlam Shalamov – brutal short stories from the Gulag that shake you to your core. I cycle between historical analyses of global events and trashy spy novels for relaxation. I just finished “The Case of Comrade Tulayev” by Victor Serge about the bizarre upside down world of the plots that were dreamt up, faux investigated, and prosecuted under Stalin. I’m currently re-reading “Number go up” by Zeke Faux about the bizarre world of the cryptobros. I read it when it came out in 2022 I think, and was shocked to hear that regions in Southeast Asia were being used by gangs to imprison hapless foreigners to take part in crypto-pig butchering scams. Still going on, and just a shocker.

What makes you the most happy these days?

Peter: My wife, my family, our two dogs, the good friends and colleagues that have continued to support me, the network of positive people like you out there who understand what this all means. Gardening, skiing, cycling, watching Youtube videos about restoring houses/watches/rewilding trashed landscapes. Working hard with our new nonprofit, Nature Health Global, to build back from the devastation these last 5 years have caused.

CLICK THE BUTTON BELOW FOR DR> WILSON TALK TO PETER DASZAK…………